From Replicators to Regulators

What a 3D-Printed Aircraft Failure Tells Us About Governing Innovation

I don’t remember the first time I watched Star Trek as a young boy of about 10, but I can remember the effect it had on me, and it probably goes some way to explain my love of science and technology. In amongst the standard sci-fi fare of warp drives, photon torpedoes and transporters, it always felt to me that there was one device which was far more crucial in creating the utopian society presented: the replicator.

Replicators, innocuous devices frequently shown but hardly mentioned, could miraculously produce anything the crew of the Starship Enterprise could need or desire, from chocolate pudding to tricorders. Being able to turn energy into material creates the kind of post-scarcity world where managing resources is no longer the limiting factor deciding how we live and work together.

3D Printing: Real-World Replicator

Modern Additive Manufacturing, more commonly called 3D Printing, might be a long way off this universal capability but it is revolutionising the way we think about manufacturing. Moving away from capable but inflexible machining processes opens up a world of possibilities for customisation, personalisation and rapidly evolving iterative design.

3D Printing is also revolutionary in how it democratises manufacturing, bringing cost effective, versatile manufacturing within the reach of small companies and individuals without having to invest significant capital into a suite of different machines.

As an engineer and general fan of tinkering, you might be surprised to hear that I have been a relatively late adopter of 3D printing at home. The technology has been present throughout my engineering career: from printed plastic parts incorporated into my Master’s degree project through to groundbreaking metal 3D printing for projects as diverse as fusion power and custom bio-medical implants.

Versus my experience in industry, what was previously available to the average Do-It-Yourselfer at home was much more limited. Temperamental machines with frequent print failures and a limited range and availability of materials meant this was a hobby for the committed and patient enthusiast, rather than a serious productivity tool. However, this has all changed over recent years with many companies providing machines which offer out-of-the box reliability and plug-and-play simplicity.

It’s something we are monitoring closing from a metrology perspective at the University of Huddersfield and from a policy perspective at ForgeFront.

Democratised Design, Distributed Risk

Simply put, you don’t need to be an engineer any more to design and model the parts to print. Vast libraries of designs are available online with parts for any conceivable application waiting to be downloaded and printed. New, creative approaches to Intellectual Property and design licensing are also evolving to cope with a blossoming cottage industry of people using their printers for commercial gain. The toys, trinkets and knick-knacks are still there in abundance (as any recent visitor to a craft fair will attest) but the pace of innovation is rapid.

The future of this trend is quickly taking shape. There is increasing availability of true ‘engineering quality’ materials with strength-to-weight properties that rival machined aluminium. This opens doors to home manufacturing of functional structural parts that rival what you might find in your local hardware store.

The rapid pace of innovation raises an important question: how do you know the design of a part is any good and how can you be sure the part is manufactured from appropriate materials to a high standard?

When we buy things from a shop, either in person or online, we trust there is a degree of quality commensurate with the price as well as robust oversight of standards. This isn’t naivety, it’s based on the historical logic that if someone took the time to design a part and then invested in the tooling to manufacture it in bulk, it must be a mature design of proven capability.

That logical trust is quickly breaking apart. When the cost to produce a one-off item is marginal and when anyone can upload designs to the internet without surveillance from authorities. 3D printing used to be called rapid prototyping for a reason. This is a risk which will gain in importance as businesses and consumers increasingly use 3D printing in their daily lives.

A 3D-Printed Aircraft Failure as a Warning Signal

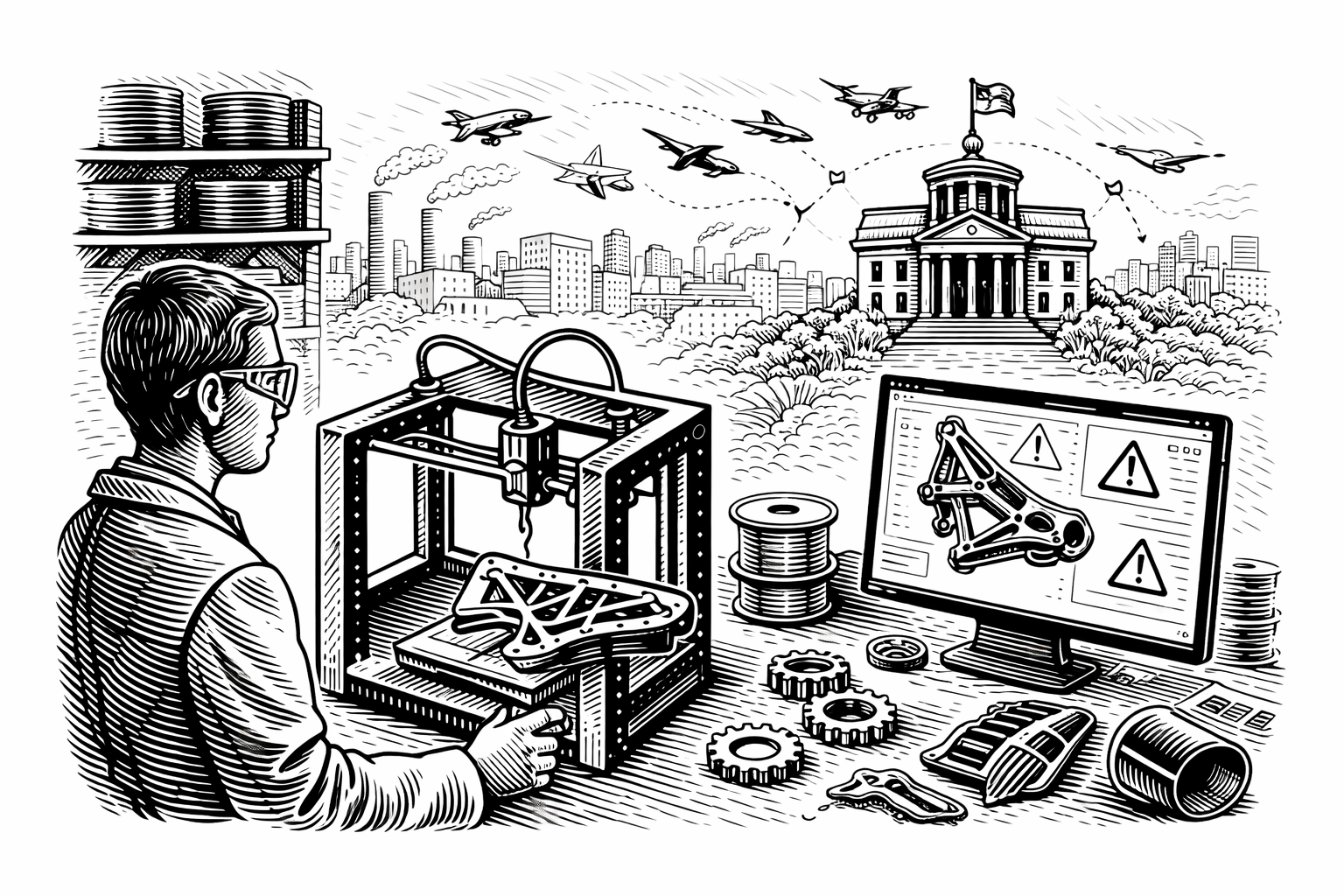

You may have seen a recent news story about the investigation into a light aircraft crash which was caused when an aftermarket 3D printed part used in the engine’s induction system softened under heat and collapsed during operation. Thank goodness no one was badly hurt.

The failure wasn’t simply because the part was plastic, the OEM part was a mixture of plastic and aluminium. The report from the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) concluded that the part failed because the material properties did not match what was expected and the design failed to incorporate sufficient strengthening to ensure the part remined rigid in service.

Seeing the part, it is a complex design, and I suspect the person who designed and made it does have some background in engineering. Nevertheless, I think we can all conclude that in this case, knowledge isn’t enough and must be backed up by testing, verification and oversight.

Governing Innovation at Warp Speed

The AAIB has rightly identified the need for greater regulation of the use of 3D printed parts in safety critical applications.

However, this reactive response to regulation misses the crucial point. The pace of innovation is increasing, and new technologies are no longer the preserve of established institutions. Human nature is nothing if not inventive and access to technologies such as 3D Printing, AI and potentially quantum will fundamentally impact on the way we interact with our built environment.

Instead of reacting to emerging trends such as these, policymakers can’t afford to wait until things go wrong. They need to minimise the risks before disaster happens through proactive regulation aided by futures and foresight techniques such as policy roadmapping and backcasting.

This will both aid innovation, as people will know the parameters in which they need to operate, but it will also save lives in a world where changes are happening at warp speed.